“I never trust anything that bleeds for five days and doesn’t die.“

Years ago, my male friend had this “SouthPark” meme on his t-shirt and at the time I had a silent, visceral response. I never said anything to him- though I viewed it as a sexist microaggression- because I feared being labeled overly sensitive.

This demonstrates the bigger problem that plagues eastern and western cultures and one rooted in misogyny- menstrual shaming.

A 35-year-old woman in Nepal, Amba Bahora, and her young sons earlier this month were found dead in a menstruation hut. She was partaking in the tradition known as chhaupadi, when menstruating women are alienated to a hut during their monthly cycle since they are considered unclean.

They remain there because it is deemed they should not be touched and should not touch anyone or anyone’s food.

Despite being a freezing Himalayan winter, she and her two sons ages 7 and 9, died in the hut from secondary smoke inhalation from a small fire they created one night to keep warm. In 2017, the Nepalese government banned the misogynistic tradition, but some smaller villages like this one still practice it.

This is also common practice in southeast Asia, Africa, and throughout the world, sometimes encouraged by religious tradition ranging from Hinduism to many of the conservative orthodox Abrahamic religions (Islam, Orthodox Christianity, and orthodox Judaism). During menstruation, women are generally considered impure and are exempt from prayer services and religious activities or entering religious buildings.

As a Muslim OB/GYN with South Asian heritage, I grew up in the late 1980s-early 1990s in the U.S. believing menstruation was unclean and that I was considered polluted during that time of month. It was never discussed in my household but it was known that I was exempt from prayer or fasting during menses. I was not able to resume until ghusl or ritual purification was performed.

As many girls after menarche, I also remember the fear and shame at school worrying if I would be ridiculed by my peers. Growing up in the South, reproductive and sexual education was still a stigmatized issue that was not addressed fully in the public school I attended. Most of the girls I knew, regardless of their cultural background, had similar feelings of embarrassment around menses.

Now in my own OB/GYN medical practice, I am very active in breaking down taboos and barriers to women’s health care whether it be by openly discussing menstrual pain or cycle heaviness, or opening discussions around sexual pain and sexual dysfunction. One of my missions is educating young girls and normalizing menses as a physiologic process that should not be shamed. I intend to do the same as I raise my own children.

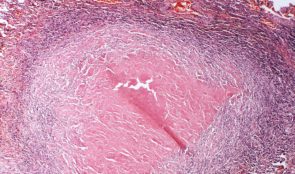

In my office, I often take care of patients who have dealt with period shaming all their lives and as a result, the pain with their cycle, or dysmenorrhea, was normalized or never discussed. Over time, these girls later become women who may have significant medical problems, and delayed diagnosis of conditions like endometriosis (where cells from the lining of your uterus are implanted in other parts of the pelvis leading to chronic pelvic pain); adenomyosis (cells from the lining of the uterus end are implanted in the muscle layers of the uterus); or uterine fibroids (benign tumors of the uterus), which can impact their quality of life, sexual life and future fertility.

This is a ubiquitous, global problem.

In May 2018, the United Nations Population Fund reported on the shame, stigma , and misinformation associated around menstruation and menstrual hygiene in East and Southern Africa and its consequences to women’s health and human rights violations.

Lack of resources, clean water, menstrual hygiene products and generalized lack of education about menstruation has led to increase in gender discrimination, school absences impacting girls’ education, child marriages (as the onset of menstruation or menarche often triggers marital relations), gender-based violence, and untreated health problems. Women who are infected with HIV have the hardest time with the stigma and are often isolated as a result.

In India, menstrual related taboo has come to the forefront of discussions in an effort to build awareness, educate and improve the quality of life for women. Due to the lack of resources and lack of education to pubescent girls and most men, girls and women in India face harsh consequences.

As any bodily fluid excreted is thought to be impure in both Hinduism and Islam, which are predominant religions in India, some of the cultural barriers to normalizing menstruation have been around for centuries and are still stigmatized.

According to UNICEF, 93 percent of girls miss an average of one to two days a month due to menstruation. Of these, 74 percent miss school because of pain. Others miss school due to fear of staining clothes and shame and embarrassment.

There are solutions to this global crisis.

Arunachalam Muruganantham, affectionately known as Pad-man, is a social entrepreneur who is credited for investing a low cost sanitary pad-making machine and generated awareness about traditional unhygienic practices around menstrual flow in rural India.

His machines manufacture sanitary pads for less than a third of the cost of the commercial pads and are already available in 23 of the 29 states in India. In 2014, he was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people. In 2018, a Bollywood movie was made about his story, “Pad Man.”

In 2014, entrepreneurs Miki Agrawal, Radha Agrawal and Antonia Dunbar launched a reusable ultra-absorbent underwear, called Thinx. The mission is to eliminate multiple hygiene products in an environmentally conscious manner as well as to raise awareness worldwide with open discussions around menses.

They also work to mitigate “period poverty” in America or globally where poor girls and women have no access to feminine hygiene products.

In the United States, as well as other developed nations, a tampon tax ensures that feminine hygiene products are subject to a sales tax in many states. It is a tax not placed on other products that are thought to be of necessity like medications or prosthesis.

In her 2017 book, Periods Gone Public: Taking A Stand For Menstrual Equity, Jennifer Weiss Wolf raises awareness to “period inequity” and her advocacy toward “tampon tax” and how it impacts “period poverty” as well.

Thankfully, menstrual shaming does not frequently result in the death of a woman and her family. But it is omnipresent for most all girls and women around the world.

Once barriers to open discussion about menses, reproductive health, and sexual pain and dysfunction are eliminated through raising awareness, eliminating sexist laws and cultural traditions, women will be able to eliminate the disgrace and embarrassment they feel surrounding natural processes that half of the world’s population endures. This may lead to earlier diagnosis and treatments of menstrual irregularities, pain and sexual dysfunction.

Sameena Rahman, M.D.is a practicing OB/GYN and owner of Center for Gynecology and Cosmetics in downtown Chicago, Clinical Assistant Professor of OB/GYN at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine and a Public Voices Fellow through The OpEd Project.

Worth your time

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos 2025

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casino Italiani Non Aams

- Online Casino Canada

- Non Gamstop Casinos Uk

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Francais

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Siti Casino Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Casino Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Siti Non Aams

- Tennis Paris Sportif

- Site De Paris Sportif En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- ブック メーカー おすすめ

- Online Casino App Real Money

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Meilleurs Casino En Ligne

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne

- Casino Con Crypto

- Best Crypto Casino