Now that the Democrats are in control of the House, they are likely to push a number of issues ranging from immigration, health care, and, of course, education. We can expect the House to increase oversight of Betsy DeVos, especially with Representative Bobby Scott of Virginia in charge of the House education committee.

Chief among the many issues Democrats will be scrutinizing should be DeVos’ policies on discrimination and bias in special education.

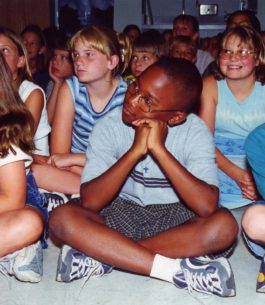

For decades, students of color – especially black, Native American, and Latino students – have been found to be overrepresented in special education and in school disciplinary practices such as suspension, expulsion, seclusion and restraint. Children of color in special education are also more likely than their white peers to be placed in the most restrictive, secluded, and segregated settings with little access to general education.

Against this backdrop, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos recently placed a hold on Equity in IDEA (the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act), a regulation developed under the Obama Administration that was supposed to be rolled out in 2018-2019. Equity in IDEA required states to apply a standard approach to determining racial disproportionality in special education; it regulated states to more accurately identify and act on significant inequity in their districts to prevent these discriminatory practices from continuing.

Although Equity in IDEA is an Obama-era rule, this concern of an unequal approach in special education is an issue that has crossed party lines. In fact, both presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush signed into law amendments to IDEA (in 1997 and 2004 respectively) that required states to collect and analyze data with increasing rigor. President Bush even issued an executive order to create a commission that examined a number of issues in special education, including disproportionality.

If racial disproportionality has been well established in research and identified as a problem by political leaders across party lines, why is the Trump administration refusing to move forward with Equity in IDEA?

DeVos’ decision relies heavily on recent research conducted by education professors Paul J. Morgan and George Farkas, who in 2015 published an opinion piece in The New York Times with the provocative title, “Is Special Education Racist?” Morgan and Farkas draw on evidence from their own research to debunk over 40 years of scholarship on this issue. The authors find that rather than being overrepresented, students of color, across racial groups and English learner status, are underrepresented in special education compared to white students after accounting for a variety of factors, such as socioeconomic status and academic achievement.

In other words, if you have a black student and a white student who are “identical” on a number of factors other than race, then the black student is less likely to be identified for special education than the white student. Morgan and Farkas thus argue that more students of color should be referred to special education, not less.

Why? Because they concluded that it’s not racial bias that leads to students of color being overrepresented in special education. Instead, it’s other factors, such as poverty, lead poisoning, and single parenthood that result in actual higher prevalence of disabilities among students of color who are more likely to experience these circumstances. In other words, they believe children of color are more likely to need services because they are not equal to their white peers.

This conclusion gives backing to a deep-seated belief in American society that has maintained white privilege in schools since public education was first conceived – that children of color are inherently lesser than their white counterparts. If, as Morgan and Farkas argue, children of color actually do have disabilities at higher rates than white students, then we should ensure that they receive the services they need.

Scholars across the country who are deeply troubled by Morgan and Farkas’ work, however, criticize this body of research as biased and misguided.

The authors promote the view that children of color are deficient, ignoring the reality that they are most likely to be overrepresented in more subjective disability categories.

Morgan and Farkas fail to acknowledge that students of color do not belong to the dominant culture of schools, and lack of whiteness in their behavior, language, and approach to schooling gets labeled as problematic. They do not consider that if poverty leads to actual disabilities, then we should see a disproportionate number of poor white students in special education as well, but we do not. What’s more, they do not recognize that even if you account for social class and academic achievement, a black student and a white student will never be an identical comparison because of structural, systemic racism.

DeVos’ freeze on Equity in IDEA means that racial bias in special education will likely continue unchecked. In fact, we may even have more students of color identified for special education given Morgan and Farkas’ work. Given that students of color in special education are more likely to drop out of school, less likely to graduate from high school, and more likely to end up in jail than their white counterparts, this means even more children will be vulnerable to the school-to-prison pipeline.

The pause on Equity in IDEA is more than a political move to undo Obama-era regulations. It is a racialized move that justifies and upholds white privilege in schools.

Soyoung Park is an Assistant Professor in Special Education at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a 2018-2019 Public Voices Fellow of the Op-Ed Project.

Worth your time

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos 2025

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casino Italiani Non Aams

- Online Casino Canada

- Non Gamstop Casinos Uk

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Francais

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Siti Casino Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Casino Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Siti Non Aams

- Tennis Paris Sportif

- Site De Paris Sportif En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- ブック メーカー おすすめ

- Online Casino App Real Money

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Meilleurs Casino En Ligne

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne

- Casino Con Crypto

- Best Crypto Casino